The “PM Press Outspoken Authors” series of chapbooks includes such writers as Cory Doctorow, Michael Moorcock, Kim Stanley Robinson—and Ursula K. Le Guin, whose book is the sixth in the series, featuring the novella “The Wild Girls,” as well as essays, poetry and an interview. Two of the pieces are previously published, but the rest are new.

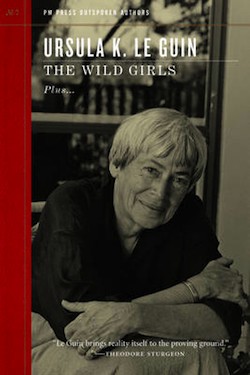

The Wild Girls Plus runs exactly 100 pages. It’s a fine little book; I was immensely satisfied with it and the variety of contents it contained. There’s something to be said about its appeal as an art-object, also, which most chapbooks strive to be in some way—it’s not overly plain or overly pretentious, but just right. The inviting photograph of Le Guin makes for a great cover, and the text of the title, credits, and series name & number are unobtrusive.

The titular novella, “The Wild Girls,” is an upsetting, evocative story, originally published in Asimov’s, which deals with the kidnapping, abuse and slavery of a pair of sisters, Mal and Modh, in an extremely hierarchical, patriarchal society. It makes no assurances, and offers no comfort—it’s a painful story, emotionally vivid and wrenching, that ends in a tragedy which will go unremarked and change nothing in the society.

In some ways, I would call it a horror story; not in the way that we generally use the term, but in the sense of a story full of horrifying things. The willful cruelty of the City people toward the nomadic tribes, whom they refer to as Dirt people, is omnipresent and made deeply personal to the reader. After all, Mal and Modh are stolen as children to be slave-wives, and Mal in the end murders the man who buys her when he tries to rape her in her bed, which results in her own death. Not only that, but she’s tossed to the dogs instead of being given a proper burial, an assurance that her spirit will come back to haunt—which it does, resulting in the childbed death of Modh at the end.

Cruelty and willful blindness on part of the patriarchal society bring about the horrors of hauntings and madness, which only sisterhood had previously abated even a little. Implicit in the terrors of the story are Le Guin’s critiques of hierarchy, patriarchy, and racism. Despite the difficulty it presents to a reader emotionally, or perhaps because of it, it’s a beautiful, intense story. Le Guin’s prose is breath-taking, and the story she tells with it equally so, though in a different way.

Following it come two essays, a handful of poems and an interview. Both of the essays are incisive, witty and well-written; one, “Staying Awake While We Read,” was first published in Harper’s Magazine. Its stand-out argument is about the appalling failure of corporate publishing in recent decades: “ to me one of the most despicable things about corporate publishing is their attitude that books are inherently worthless.” (68) She continues to enumerate the ways in which corporations have misunderstood how book publishing works, gutting midlists and backlists, devaluing art and artists, et cetera. It’s a brilliant take-down of corporation-style publishing.

Next come the poems; all short works, each with a theme slightly different from the others. The one that struck me the hardest was “Peace Vigils,” on the hopelessness and hopefulness of continuing to try in the face of metaphorical, implacable rains. The rest are also moving, including the more experimental piece, “The City of the Plain,” which has a powerful ending stanza.

Another essay follows, “The Conversation of the Modest,” which deals with Le Guin’s strong ideas about what modesty actually is and means, and what the value of it can be if conceived of properly. It takes to task the misuses of the word “modesty” to trample the rights of women, and reinterprets it for the artist as a valuable ability to truly evaluate one’s work without too much self-doubt or too much self-confidence. It’s a neat little essay, drawing finally on ideas of community and conversation in relation to the value of modesty, and I find Le Guin’s candor in it especially refreshing.

The last bit of the chapbook is the Outspoken Interview, titled “A Lovely Art.” I adored this bizarre, sometimes off-the-wall interview, which also asked some great questions—or, questions that got great answers. For example, a favorite of mine:

“Even though you occupy a pretty high perch in American Letters, you have never hesitated to describe yourself as a science-fiction and fantasy author. Are you just being nice, or is there a plot behind this?

I am nice.

Also, the only means I have to stop ignorant snobs from behaving towards genre fiction with snobbish ignorance is to not reinforce their ignorance and snobbery by lying and saying that when I write SF it isn’t SF, but to tell them more or less patiently for forty or fifty years that they are wrong to exclude SF and fantasy from literature, and proving my argument by writing well.” (83)

That’s fabulous, is what that is. As I’ve said earlier in this appreciation, Le Guin is incisive and witty—and that’s on full display in this interview. She speaks the truth, as openly and clearly as she possibly can. The questions range from her reading habits to her writing habits to theories about life and time, plus some other stuff like what kind of car she drives. To be perfectly honest, I would have bought this fairly-priced chapbook for this interview and the novella alone; the essays and poetry make it doubly worthwhile.

I appreciate that there are publishers making little neat books like this one, with a mixture of contents that span the different writing-hats a person like Le Guin has worn in her career. Too often books are restricted to one sort of thing; a fiction collection, or an essay collection, or a poetry collection. The Wild Girls Plus is all of these things, and provides an enjoyable, worthwhile reading experience, especially for existing fans of Le Guin like myself.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.